- We will send in 10–14 business days.

- Author: R Bentley Anderson

- Publisher: Vanderbilt University Press

- ISBN-10: 0826514847

- ISBN-13: 9780826514844

- Format: 15.2 x 23.1 x 2 cm, softcover

- Language: English

- SAVE -10% with code: EXTRA

Reviews

Description

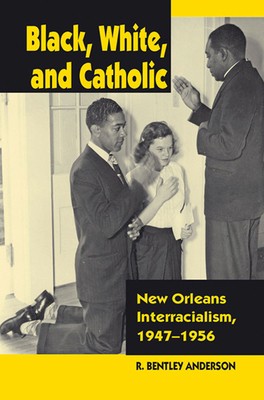

Most histories of the Civil Rights Movement start with all the players in place--among them organized groups of African Americans, White Citizens' Councils, nervous politicians, and religious leaders struggling to find the right course. Anderson, however, takes up the historical moment right before that, when small groups of black and white Catholics in the city of New Orleans began efforts to desegregate the archdiocese, and the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) began, in fits and starts, to integrate quietly the New Orleans Province.

Anderson leads readers through the tumultuous years just after World War II when the Roman Catholic Church in the American South struggled to reconcile its commitment to social justice with the legal and social heritage of Jim Crow society. Though these early efforts at reform, by and large, failed, they did serve to galvanize Catholic supporters and opponents of the Civil Rights Movement and provided a model for more successful efforts at desegregation in the '60s.

As a Jesuit himself, Anderson has access to archives that remain off-limits to other scholars. His deep knowledge of the history of the Catholic Church also allows him to draw connections between this historical period and the present. In the resistance to desegregation, Anderson finds expression of a distinctly American form of Catholicism, in which lay people expect Church authorities to ratify their ideas and beliefs in an almost democratic fashion. The conflict he describes is as much between popular and hierarchical models of the Church as between segregation and integration.

This book has been made possible through a grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

EXTRA 10 % discount with code: EXTRA

The promotion ends in 18d.17:45:16

The discount code is valid when purchasing from 10 €. Discounts do not stack.

- Author: R Bentley Anderson

- Publisher: Vanderbilt University Press

- ISBN-10: 0826514847

- ISBN-13: 9780826514844

- Format: 15.2 x 23.1 x 2 cm, softcover

- Language: English English

Most histories of the Civil Rights Movement start with all the players in place--among them organized groups of African Americans, White Citizens' Councils, nervous politicians, and religious leaders struggling to find the right course. Anderson, however, takes up the historical moment right before that, when small groups of black and white Catholics in the city of New Orleans began efforts to desegregate the archdiocese, and the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) began, in fits and starts, to integrate quietly the New Orleans Province.

Anderson leads readers through the tumultuous years just after World War II when the Roman Catholic Church in the American South struggled to reconcile its commitment to social justice with the legal and social heritage of Jim Crow society. Though these early efforts at reform, by and large, failed, they did serve to galvanize Catholic supporters and opponents of the Civil Rights Movement and provided a model for more successful efforts at desegregation in the '60s.

As a Jesuit himself, Anderson has access to archives that remain off-limits to other scholars. His deep knowledge of the history of the Catholic Church also allows him to draw connections between this historical period and the present. In the resistance to desegregation, Anderson finds expression of a distinctly American form of Catholicism, in which lay people expect Church authorities to ratify their ideas and beliefs in an almost democratic fashion. The conflict he describes is as much between popular and hierarchical models of the Church as between segregation and integration.

This book has been made possible through a grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Reviews